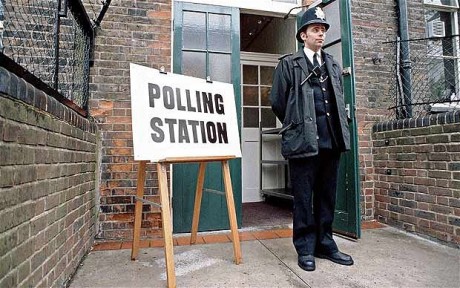

So prisoners will not get the vote. David Cameron has pledged against it, in defiance of the European Court of Human Rights ruling, and despite the protestations of Dominic Grieve, the attorney general, who has pointed out that Britain was legally obliged to uphold the European diktat. No: the Prime Minister sets his store by last year’s vote in which MPs agreed by 234 to 22 to keep prisoners away from the ballot box.

On the surface, this issue appears to be simply another self-contained instance of friction between London and Europe. But it is more than that. In reality, it is an expression of a fundamental – and controversial – philosophical question: Does every citizen really deserve to vote? If so, why?

This issue has been explored by Jennifer L. Hochschild, Professor of Government at Harvard. In 2010, she published a study entitled If democracies need informed voters, how can they thrive while expanding enfranchisement?, which suggests that “as democracies become more democratic [by giving the vote to disenfranchised groups], their decision-making processes become of lower quality in terms of cognitive processing of issues and candidate choice”. Although it is an unassailable ideal of democracy to govern by consent of the entire populace, the more that access to the vote is liberalised, the less responsible the electorate becomes, and the more volatile their decisions. If prisoners were allowed to vote, for instance, the future of our country would, to some small extent, rely upon their judgment.

It is inevitable that the rot will spread, and political culture will reflect the increasingly superficial attitudes of the electorate. We live in the age of personality politics, where the sound bite is king; Hochschild’s observations suggest that this may be linked to the “lower quality” of the voting public, as well as the advent and prevalence of mass media, particularly television. The American presidential debates are a case in point. Last week, I wrote about the many Americans who may watch the televised debates mainly to confirm their existing bias, and take only superficial observations from them. Gabriel S Lenz and Chappell Lawson, academics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), have supported this in a study entitled “Looking the part: television leads less informed citizens to vote based on candidates’ appearance.”

“As long as there has ben democratic government,” they write, “sceptics have worried that citizens would base their choices and their votes on superficial consideration.” The age of the television, they conclude, has made this fear a reality. “Since the advent of television, political observers have fretted about the degree to which it privileges image over substance. The results we report appear to confirm that some of these long-standing fears.”

Barack Obama is the undisputed master of political presentation. His 2008 “hope” campaign was an object lesson in inspiring the electorate with confidence, regardless of the viability of one’s policies. This time round, he appears to be trying to do the same again. His campaign slogan, “Forward.”, with its widely ridiculed full stop, may just represent a faded facsimile of the élan of 2008, but his fundamental approach has not changed. Few Americans, even the intelligentsia, have any idea what another four years of Obama might entail. But they know what his sound bites are.

The televised debates have driven this home, with the candidates arguing over the most obscure and elliptical points – precisely where and when companies should be allowed to drill for oil, and the intricacies of economic recovery – about which even expert economists disagree, while the President’s main policy planks remain a mystery. As for the voters, they are left to make up their minds based on slogans, personality, and whether the candidates look tired or energised on the day.

That’s not to say that there is no place for gut feeling when casting a vote. The president – or prime minister – will, after all, have a finger on the nuclear button, and it would be a mistake to support a candidate who appears untrustworthy or unpleasant, whatever their policy pledges. The problem arises, however, when a less-informed voting public allows these emotive reactions to outweigh and eclipse the manifestos themselves.

Pollsters have routinely demonstrated that large numbers of Americans have very little knowledge about how their political system works. Substantial numbers believe, for example, that the federal government spends 30 per cent of its budget on foreign aid, and that the president is a Muslim socialist. Indeed, when a 2010 University of Maryland poll asked the American public for their ideal level of spending on foreign aid, most Americans said that it should be “cut” to between 10 and 13 per cent of the overall budget (it currently stands at around 1 per cent).

According to Jason Brennan, a professor of political philosophy at Brown University and author of The Ethics of Voting, it would be better for society if the ill-informed do not vote. After all, he argues, voting is about deciding how other people should live. “If most voters decide, ‘We don’t know anything, we’re just going to kind of choose whatever we find emotionally appealing,’ then they’re imposing that upon other people,” he says. “I’ve actually become more sympathetic to the idea that maybe people should be formally excluded from voting.” One of his more potent metaphors compares the badly informed voter to a drunk driver. It would seem that David Cameron, in pledging that prisoners will not be allowed the vote, has shades of a similar view. The demands of the European Court of Human Rights may be falling on deaf ears; but shouldn’t we also address the question of whether a vote should be conferred on every citizen as a matter of course?

Democracy, as Churchill observed, is “the least bad option”. One of its principle failings is the fact that the vote of a person holding racist views, for instance, will count as equal to that of an enlightened political observer. This both dignifies the former unfairly, and dilutes the efficacy of the latter.

The notion of restricting the electorate, however, leaves a bad taste in the mouth, and almost seems to have a whiff of eugenics about it.

Moreover, to set up an official body to judge whether or not people deserve the vote would be to create significant potential for abuse by those seeking to further their own political interests. Alex Salmond, in lobbying to extend access to the Scottish referendum to voters aged 16 – who he hopes will be easier persuaded to vote for independence – has attempted to tilt the scales in his favour. What would happen if the government had the power to choose wholescale who can and cannot vote? For these reasons, it is unlikely that a proposed policy of earning the right to vote, rather than simply being granted it unquestioningly, would ever see the light of day.

Nevertheless, it is compelling to imagine a state of affairs in which citizens sit a simple test to demonstrate that they have a basic knowledge of the parties that are running, and the essential contours of their manifestos, before qualifying to vote. It wouldn’t need anything too complicated. Three questions would suffice, and the test could be taken online in minutes. Candidates could be asked, for instance, to declare which party is currently in power; to name the leaders of the main political parties; and to match basic election pledges to the correct party. This, in addition to weeding out the woefully ill-informed, would focus the minds of the electorate on the key matters at stake before they cast their votes.

Some might be concerned that this may discourage many from voting at all. Voter numbers have been in more or less consistent decline in recent decades, and an online test may do little to reverse that trend. But why is it assumed that the more people who vote the better? Voting is more than just an expression of personal preference on whether, say, benefits should be cut or gay marriage should be legalised. It is an opportunity to make a particular decision, within a particular context, on a particular set of questions, and a level of knowledge and engagement is vital. Of course, politicians may not follow through on their election promises, and the world of politics is often an opaque and murky one; I am not suggesting that the failures of state education and the misdemeanours of politicians are blameless in fostering voter apathy. But in the final analysis, if someone can’t be bothered to get off the sofa and make an effort for their democracy, do they really deserve a say in the future of their country?

O bijuterie de articol!