PNL, PDL, FC, PNȚcd, NR și MP nu trebuie să inventeze roata. Trebuie doar să ia clasamentul detaliat al statelor lumii făcut pe criteriul libertății economice de Heritage Foundation, să aleagă primele clasate pe orice domeniu, să facă un studiu comparativ, să determine cauzele gradului înalt de libertate economică și să le introducă în propriul program, urmînd ca atunci cînd ajung la guvernare să le și implementeze. Repet, nu trebuie să inventăm roata.

Uite, ca să le ușurez munca, fac eu lista cu cei mai liberi și mai capitaliști:

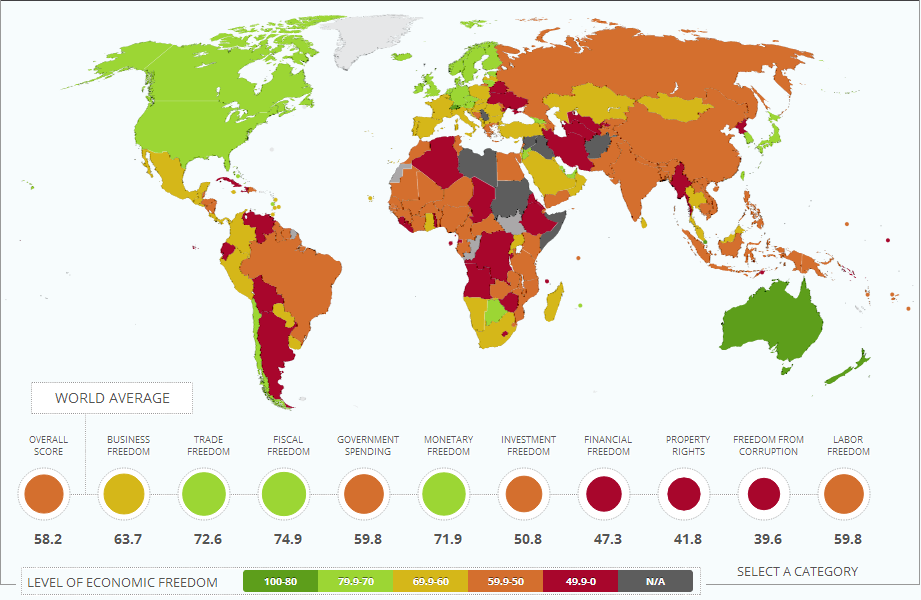

| Stat | TOTAL | property rights | freedom from corruption | government spending | fiscal freedom | business freedom | labor freedom | monetary freedom | trade freedom | investment freedom | financial freedom |

| HONG KONG | 89,3 | 90,0 | 84,0 | 88,9 | 92,9 | 98,9 | 86,2 | 82,1 | 90,0 | 90,0 | 90,0 |

| SINGAPORE | 88,0 | 90,0 | 92,0 | 91,3 | 91,1 | 97,1 | 91,4 | 82,0 | 90,0 | 75,0 | 80,0 |

| AUSTRALIA | 82,6 | 90,0 | 88,0 | 62,8 | 66,4 | 95,5 | 83,5 | 83,8 | 86,2 | 80,0 | 90,0 |

| NOUA ZEELANDĂ | 81,4 | 95,0 | 95,0 | 33,2 | 71,5 | 99,9 | 89,5 | 83,3 | 86,8 | 80,0 | 80,0 |

| ELVEȚIA | 81,0 | 90,0 | 88,0 | 63,8 | 68,1 | 75,8 | 87,9 | 86,2 | 90,0 | 80,0 | 80,0 |

| CANADA | 79,4 | 90,0 | 87,0 | 44,8 | 79,8 | 91,7 | 82,3 | 75,2 | 88,2 | 75,0 | 80,0 |

| CHILE | 79,0 | 90,0 | 72,0 | 83,7 | 77,6 | 70,5 | 74,2 | 84,6 | 82,0 | 85,0 | 70,0 |

| MAURITIUS | 76,9 | 70,0 | 51,0 | 81,9 | 92,1 | 78,2 | 72,3 | 75,4 | 87,9 | 90,0 | 70,0 |

| DANEMARCA | 76,1 | 90,0 | 94,0 | 5,9 | 39,8 | 98,4 | 91,1 | 80,0 | 86,8 | 85,0 | 90,0 |

| STATELE UNITE | 76,0 | 85,0 | 71,0 | 47.8 | 69,3 | 90,5 | 95,5 | 75,0 | 86,4 | 70,0 | 70,0 |

| ROMÂNIA | 65,1 | 40,0 | 36,0 | 62,2 | 87,9 | 70,4 | 63,5 | 74,7 | 86,8 | 80,0 | 50,0 |

Property Rights

The more certain the legal protection of property, the higher a country’s score; similarly, the greater the chances of government expropriation of property, the lower a country’s score. Countries that fall between two categories may receive an intermediate score.

Each country is graded according to the following criteria:

- 100—Private property is guaranteed by the government. The court system enforces contracts efficiently and quickly. The justice system punishes those who unlawfully confiscate private property. There is no corruption or expropriation.

- 90—Private property is guaranteed by the government. The court system enforces contracts efficiently. The justice system punishes those who unlawfully confiscate private property. Corruption is nearly nonexistent, and expropriation is highly unlikely.

- 80—Private property is guaranteed by the government. The court system enforces contracts efficiently but with some delays. Corruption is minimal, and expropriation is highly unlikely.

- 70—Private property is guaranteed by the government. The court system is subject to delays and is lax in enforcing contracts. Corruption is possible but rare, and expropriation is unlikely.

- 60—Enforcement of property rights is lax and subject to delays. Corruption is possible but rare, and the judiciary may be influenced by other branches of government. Expropriation is unlikely.

- 50—The court system is inefficient and subject to delays. Corruption may be present, and the judiciary may be influenced by other branches of government. Expropriation is possible but rare.

- 40—The court system is highly inefficient, and delays are so long that they deter the use of the court system. Corruption is present, and the judiciary is influenced by other branches of government. Expropriation is possible.

- 30—Property ownership is weakly protected. The court system is highly inefficient. Corruption is extensive, and the judiciary is strongly influenced by other branches of government. Expropriation is possible.

- 20—Private property is weakly protected. The court system is so inefficient and corrupt that outside settlement and arbitration is the norm. Property rights are difficult to enforce. Judicial corruption is extensive. Expropriation is common.

- 10—Private property is rarely protected, and almost all property belongs to the state. The country is in such chaos (for example, because of ongoing war) that protection of property is almost impossible to enforce. The judiciary is so corrupt that property is not protected effectively. Expropriation is common.

- 0—Private property is outlawed, and all property belongs to the state. People do not have the right to sue others and do not have access to the courts. Corruption is endemic.

Freedom from Corruption

Corruption erodes economic freedom by introducing insecurity and uncertainty into economic relationships. The score for this component is derived primarily from Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2011, which measures the level of corruption in 183 countries.

The CPI is based on a 10-point scale in which a score of 10 indicates very little corruption and a score of 0 indicates a very corrupt government. In scoring freedom from corruption, the Index converts the raw CPI data to a scale of 0 to 100 by multiplying the CPI score by 10. For example, if a country’s raw CPI data score is 5.5, its overall freedom from corruption score is 55.

For countries that are not covered in the CPI, the freedom from corruption score is determined by using the qualitative information from internationally recognized and reliable sources. This procedure considers the extent to which corruption prevails in a country. The higher the level of corruption, the lower the level of overall economic freedom and the lower a country’s score.

Government Spending

This component considers the level of government expenditures as a percentage of GDP. Government expenditures, including consumption and transfers, account for the entire score.

No attempt has been made to identify an optimal level of government expenditures. The ideal level will vary from country to country, depending on factors ranging from culture to geography to level of development. However, volumes of research have shown that excessive government spending that causes chronic budget deficits and the accumulation of sovereign debt is one of the most serious drags on economic dynamism.

The methodology treats zero government spending as the benchmark, and underdeveloped countries with little government capacity may receive artificially high scores as a result. However, such governments, which can provide few if any public goods, are likely to receive lower scores on some of the other components of economic freedom (such as property rights, financial freedom, and investment freedom) that reflect government effectiveness.

The scale for scoring government spending is non-linear, which means that government spending that is close to zero is lightly penalized, while levels of government spending that exceed 30 percent of GDP lead to much worse scores in a quadratic fashion (for example, doubling spending yields four times less freedom). Only extraordinarily large levels of government spending—for example, over 58 percent of GDP—receive a score of zero.

The expenditure equation used is:

GEi = 100 – α (Expendituresi)2

where GEi represents the government expenditure score in country i; Expendituresi represents the total amount of government spending at all levels as a portion of GDP (between 0 and 100); and α is a coefficient to control for variation among scores (set at 0.03). The minimum component score is zero.

In most cases, general government expenditure data include all levels of government such as federal, state, and local. In cases where general government spending data are not available, data on central government expenditures are used instead.

Fiscal Freedom

Fiscal freedom is a measure of the tax burden imposed by government. It includes direct taxes, in terms of the top marginal tax rates on individual and corporate incomes, and overall taxes, including all forms of direct and indirect taxation at all levels of government, as a percentage of GDP. Thus, the fiscal freedom component is composed of three quantitative factors:

- The top marginal tax rate on individual income,

- The top marginal tax rate on corporate income, and

- The total tax burden as a percentage of GDP.

In scoring fiscal freedom, each of these numerical variables is weighted equally as one-third of the component. This equal weighting allows a country to achieve a score as high as 67 based on two of the factors even if it receives a score of 0 on the third.Fiscal freedom scores are calculated with a quadratic cost function to reflect the diminishing revenue returns from very high rates of taxation. The data for each factor are converted to a 100-point scale using the following equation:

Fiscal Freedomij= 100 – α (Factorij)2

where Fiscal Freedomij represents the fiscal freedom in country i for factor j; Factorij represents the value (based on a scale of 0 to 100) in country i for factor j; and α is a coefficient set equal to 0.03. The minimum score for each factor is zero, which is not represented in the printed equation but was utilized because it means that no single high tax burden will make the other two factors irrelevant.

As an example, in the 2013 Index, Mauritius has a flat rate of 15 percent for both individual and corporate tax rates, which yields a score of 93.3 for each of the two factors. Mauritius’s overall tax burden as a portion of GDP is 18.5 percent, yielding a tax burden factor score of 89.7. When the three factors are averaged together, Mauritius’s overall fiscal freedom score becomes 92.1.

Business Freedom

- Starting a business—procedures (number);

- Starting a business—time (days);

- Starting a business—cost (% of income per capita);

- Starting a business—minimum capital (% of income per capita);

- Obtaining a license—procedures (number);

- Obtaining a license—time (days);

- Obtaining a license—cost (% of income per capita);

- Closing a business—time (years);

- Closing a business—cost (% of estate); and

- Closing a business—recovery rate (cents on the dollar).

Each of these raw factors is converted to a scale of 0 to 100, after which the average of the converted values is computed. The result represents the country’s business freedom score. For example, even if a country requires the highest number of procedures for starting a business, which yields a score of zero in that factor, it could still receive a score as high as 90 based on scores in the other nine factors. Canada, for instance, receives scores of 100 in nine of these 10 factors, but the 14 licensing procedures required by the government equate to a score of 64.5 for that factor.

Each factor is converted to a scale of 0 to 100 using the following equation:

Factor Scorei = 50 factoraverage/factori

which is based on the ratio of the country data for each factor relative to the world average, multiplied by 50. For example, on average worldwide, it takes 18 procedures to get necessary licenses. Canada’s 14 licensing procedures are a factor value better than the average, resulting in a ratio of 1.29. That ratio multiplied by 50 equals the final factor score of 64.5.

For the six countries that are not covered by the World Bank’s Doing Business report, business freedom is scored by analyzing business regulations based on qualitative information from reliable and internationally recognized sources.

Labor Freedom

The labor freedom component is a quantitative measure that considers various aspects of the legal and regulatory framework of a country’s labor market, including regulations concerning minimum wages, laws inhibiting layoffs, severance requirements, and measurable regulatory restraints on hiring and hours worked.

Six quantitative factors are equally weighted, with each counted as one-sixth of the labor freedom component:1

- Ratio of minimum wage to the average value added per worker,

- Hindrance to hiring additional workers,

- Rigidity of hours,

- Difficulty of firing redundant employees,

- Legally mandated notice period, and

- Mandatory severance pay.

Based on data collected in connection with the World Bank’s Doing Business study, these factors specifically examine labor regulations that affect “the hiring and redundancy of workers and the rigidity of working hours.”

In constructing the labor freedom score, each of the six factors is converted to a scale of 0 to 100 based on the following equation:

Factor Scorei= 50 × factoraverage/factori

where country i data are calculated relative to the world average and then multiplied by 50. The six factor scores are then averaged for each country, yielding a labor freedom score.

The simple average of the converted values for the six factors is computed for the country’s overall labor freedom score. For example, even if a country had the worst rigidity of hours in the world with a zero score for that factor, it could still get a score as high as 83.3 based on the other five factors.

For the six countries that are not covered by the World Bank’s Doing Business study, the labor freedom component is scored by looking into labor market flexibility based on qualitative information from other reliable and internationally recognized sources.

Monetary Freedom

The score for the monetary freedom component is based on two factors:

- The weighted average inflation rate for the most recent three years and

- Price controls.

The weighted average inflation rate for the most recent three years serves as the primary input into an equation that generates the base score for monetary freedom. The extent of price controls is then assessed as a penalty of up to 20 points subtracted from the base score. The two equations used to convert inflation rates into the monetary freedom score are:

Weighted Avg. Inflationi = θ1 Inflationit + θ2Inflationit–1 + θ3 Inflationit–2

Monetary Freedomi = 100 – α √Weighted Avg. Inflationi – PC penaltyi

where θ1 through θ3 (thetas 1–3) represent three numbers that sum to 1 and are exponentially smaller in sequence (in this case, values of 0.665, 0.245, and 0.090, respectively); Inflationit is the absolute value of the annual inflation rate in country i during year t as measured by the consumer price index; α represents a coefficient that stabilizes the variance of scores; and the price control (PC) penalty is an assigned value of 0–20 points based on the extent of price controls.

The convex (square root) functional form was chosen to create separation among countries with low inflation rates. A concave functional form would essentially treat all hyperinflations as equally bad, whether they were 100 percent price increases annually or 100,000 percent, whereas the square root provides much more gradation. The α coefficient is set to equal 6.333, which converts a 10 percent inflation rate into a freedom score of 80.0 and a 2 percent inflation rate into a score of 91.0.

Trade Freedom

Trade freedom is a composite measure of the absence of tariff and non-tariff barriers that affect imports and exports of goods and services. The trade freedom score is based on two inputs:

- The trade-weighted average tariff rate and

- Non-tariff barriers (NTBs).

Different imports entering a country can, and often do, face different tariffs. The weighted average tariff uses weights for each tariff based on the share of imports for each good. Weighted average tariffs are a purely quantitative measure and account for the basic calculation of the score using the following equation:

Trade Freedomi = (((Tariffmax–Tariffi )/(Tariffmax–Tariffmin )) * 100) – NTBi

where Trade Freedomi represents the trade freedom in country i; Tariffmax and Tariffmin represent the upper and lower bounds for tariff rates (%); and Tariffi represents the weighted average tariff rate (%) in country i. The minimum tariff is naturally zero percent, and the upper bound was set as 50 percent. An NTB penalty is then subtracted from the base score. The penalty of 5, 10, 15, or 20 points is assigned according to the following scale:

- 20—NTBs are used extensively across many goods and services and/or act to effectively impede a significant amount of international trade.

- 15—NTBs are widespread across many goods and services and/or act to impede a majority of potential international trade.

- 10—NTBs are used to protect certain goods and services and impede some international trade.

- 5—NTBs are uncommon, protecting few goods and services, and/or have very limited impact on international trade.

- 0—NTBs are not used to limit international trade.

We determine the extent of NTBs in a country’s trade policy regime using both qualitative and quantitative information. Restrictive rules that hinder trade vary widely, and their overlapping and shifting nature makes their complexity difficult to gauge. The categories of NTBs considered in our penalty include:

- Quantity restrictions—import quotas; export limitations; voluntary export restraints; import–export embargoes and bans; countertrade, etc.

- Price restrictions—antidumping duties; countervailing duties; border tax adjustments; variable levies/tariff rate quotas.

- Regulatory restrictions—licensing; domestic content and mixing requirements; sanitary and phytosanitary standards (SPSs); safety and industrial standards regulations; packaging, labeling, and trademark regulations; advertising and media regulations.

- Investment restrictions—exchange and other financial controls.

- Customs restrictions—advance deposit requirements; customs valuation procedures; customs classification procedures; customs clearance procedures.

- Direct government intervention—subsidies and other aid; government industrial policy and regional development measures; government-financed research and other technology policies; national taxes and social insurance; competition policies; immigration policies; government procurement policies; state trading, government monopolies, and exclusive franchises.

As an example, Botswana received a trade freedom score of 79.7. By itself, Botswana’s weighted average tariff of 5.2 percent would have yielded a score of 89.7, but the existence of NTBs in Botswana reduced the score by 10 points.

Gathering tariff statistics to make a consistent cross-country comparison is a challenging task. Unlike data on inflation, for instance, countries do not report their weighted average tariff rate or simple average tariff rate every year; in some cases, the most recent year for which a country reported its tariff data could be as far back as 2002. To preserve consistency in grading the trade policy component, the Index uses the most recently reported weighted average tariff rate for a country from our primary source. If another reliable source reports more updated information on the country’s tariff rate, this fact is noted, and the grading of this component may be reviewed if there is strong evidence that the most recently reported weighted average tariff rate is outdated.

The World Bank publishes the most comprehensive and consistent information on weighted average applied tariff rates. When the weighted average applied tariff rate is not available, the Index uses the country’s average applied tariff rate; and when the country’s average applied tariff rate is not available, the weighted average or the simple average of most favored nation (MFN) tariff rates is used. In the very few cases where data on duties and customs revenues are not available, data on international trade taxes or an estimated effective tariff rate are used instead. In all cases, an effort is made to clarify the type of data used and the different sources for those data in the corresponding write-up for the trade policy component.

Investment Freedom

Investment Freedom

In an economically free country, there would be no constraints on the flow of investment capital. Individuals and firms would be allowed to move their resources into and out of specific activities, both internally and across the country’s borders, without restriction. Such an ideal country would receive a score of 100 on the investment freedom component of the Index of Economic Freedom.

In practice, most countries have a variety of restrictions on investment. Some have different rules for foreign and domestic investment; some restrict access to foreign exchange; some impose restrictions on payments, transfers, and capital transactions; in some, certain industries are closed to foreign investment. Labor regulations, corruption, red tape, weak infrastructure, and political and security conditions can also affect the freedom that investors have in a market.

The Index evaluates a variety of restrictions that are typically imposed on investment. Points, as indicated below, are deducted from the ideal score of 100 for each of the restrictions found in a country’s investment regime. It is not necessary for a government to impose all of the listed restrictions at the maximum level to effectively eliminate investment freedom. Those few governments that impose so many restrictions that they total more than 100 points in deductions have had their scores set at zero.

Investment restrictions:

National treatment of foreign investment

| • No national treatment, prescreening | 25 points deducted |

| • Some national treatment, some prescreening | 15 points deducted |

| • Some national treatment or prescreening | 5 points deducted |

Foreign investment code

| • No transparency and burdensome bureaucracy | 20 points deducted |

| • Inefficient policy implementation and bureaucracy | 10 points deducted |

| • Some investment laws and practices non-transparent or inefficiently implemented |

5 points deducted |

Restrictions on land ownership

| • All real estate purchases restricted | 15 points deducted |

| • No foreign purchases of real estate | 10 points deducted |

| • Some restrictions on purchases of real estate | 5 points deducted |

Sectoral investment restrictions

| • Multiple sectors restricted | 20 points deducted |

| • Few sectors restricted | 10 points deducted |

| • One or two sectors restricted | 5 points deducted |

Expropriation of investments without fair compensation

| • Common with no legal recourse | 25 points deducted |

| • Common with some legal recourse | 15 points deducted |

| • Uncommon but occurs | 5 points deducted |

Foreign exchange controls

| • No access by foreigners or residents | 25 points deducted |

| • Access available but heavily restricted | 15 points deducted |

| • Access available with few restrictions | 5 points deducted |

Capital controls

| • No repatriation of profits; all transactions require government approval |

25 points deducted |

| • Inward and outward capital movements require approval and face some restrictions |

15 points deducted |

| • Most transfers approved with some restrictions | 5 points deducted |

Up to an additional 20 points may be deducted for security problems, a lack of basic investment infrastructure, or other government policies that indirectly burden the investment process and limit investment freedom.

Financial Freedom

In an ideal banking and financing environment where a minimum level of government interference exists, independent central bank supervision and regulation of financial institutions are limited to enforcing contractual obligations and preventing fraud. Credit is allocated on market terms, and the government does not own financial institutions. Financial institutions provide various types of financial services to individuals and companies. Banks are free to extend credit, accept deposits, and conduct operations in foreign currencies. Foreign financial institutions operate freely and are treated the same as domestic institutions.

The Index scores an economy’s financial freedom by looking into the following five broad areas:

- The extent of government regulation of financial services,

- The degree of state intervention in banks and other financial firms through direct and indirect ownership,

- The extent of financial and capital market development,

- Government influence on the allocation of credit, and

- Openness to foreign competition.

These five areas are considered to assess an economy’s overall level of financial freedom that ensures easy and effective access to financing opportunities for people and businesses in the economy. An overall score on a scale of 0 to 100 is given to an economy’s financial freedom through deductions from the ideal score of 100.

- 100—Negligible government interference.

- 90—Minimal government interference. Regulation of financial institutions is minimal but may extend beyond enforcing contractual obligations and preventing fraud.

- 80—Nominal government interference. Government ownership of financial institutions is a small share of overall sector assets. Financial institutions face almost no restrictions on their ability to offer financial services.

- 70—Limited government interference. Credit allocation is influenced by the government, and private allocation of credit faces almost no restrictions. Government ownership of financial institutions is sizeable. Foreign financial institutions are subject to few restrictions.

- 60—Significant government interference. The central bank is not fully independent, its supervision and regulation of financial institutions are somewhat burdensome, and its ability to enforce contracts and prevent fraud is insufficient. The government exercises active ownership and control of financial institutions with a significant share of overall sector assets. The ability of financial institutions to offer financial services is subject to some restrictions.

- 50—Considerable government interference. Credit allocation is significantly influenced by the government, and private allocation of credit faces significant barriers. The ability of financial institutions to offer financial services is subject to significant restrictions. Foreign financial institutions are subject to some restrictions.

- 40—Strong government interference. The central bank is subject to government influence, its supervision of financial institutions is heavy-handed, and its ability to enforce contracts and prevent fraud is weak. The government exercises active ownership and control of financial institutions with a large minority share of overall sector assets.

- 30—Extensive government interference. Credit allocation is extensively influenced by the government. The government owns or controls a majority of financial institutions or is in a dominant position. Financial institutions are heavily restricted, and bank formation faces significant barriers. Foreign financial institutions are subject to significant restrictions.

- 20—Heavy government interference. The central bank is not independent, and its supervision of financial institutions is repressive. Foreign financial institutions are discouraged or highly constrained.

- 10—Near repressive. Credit allocation is controlled by the government. Bank formation is restricted. Foreign financial institutions are prohibited.

- 0—Repressive. Supervision and regulation are designed to prevent private financial institutions. Private financial institutions are prohibited.

SURSA: HERITAGE FOUNDATION

Programe și guvernare de dreapta? Greu. Titlul articolului ar trebui să fie „Top 10 țări în care să emigrezi după ce ai eșuat în politica din România”.

Beavix , grozav e Bleen ! A propus să ne îmbarcăm spre NZ sau Mauritius și le regăsesc aici pe ambele! Plus că o fi soare și frumos.

Yeba Beavix Bleen nu mai spune „soare si frumos”, ca ne trezim cu raidoree-ul lui Baconschi

E ceva putred în Danemarca la Government Spending 🙂 5,9?! Sună ireal!!!

meiozaThe top income tax rate is 56 percent, and the top corporate tax rate is 25 percent. Other taxes include a value-added tax (VAT) and intrusive measures such as the world’s first tax on fatty foods. The overall tax burden equals almost 50 percent of total domestic income. Government spending continues to be over 55 percent of GDP. The government has attempted fiscal stimulus, running a small deficit, and public debt is just under 50 percent of GDP.

meioza Și Chile (scor 83.7 la government spending și 77.6 la fiscal freedom):

The top income tax rate is 40 percent. The corporate tax rate increase instituted in 2010 was temporarily lifted during the first half of 2012. Other taxes include a value-added tax (VAT) and a property tax. The overall tax burden equals 17.3 percent of GDP. Government spending is 23.3 percent of total domestic output. Public debt is about 10 percent of GDP.

On topic

Le-am găsit poziționările doctrinare lui MRU și Neamțu: centru confuz și respectiv verde cămășiu.

Si atunci care mai e obiectul muncii aparatului de stat supradimensionat? doar nu vrei sa-i trimiti la munca pe bune.